The padded comfort of Edwardian matrimonial conventions is where George Bernard Shaw’s Getting Married lands like a sharp, accurate scalpel. The play, which was first performed in 1908, reads more like a daringly structured argument than a celebration of romantic unions. It is a verbal battleground where characters grapple with agreements, repercussions, and the nuances of what society defines as love.

The story revolves around Edith and Cecil, a couple who refuse to leave their rooms due to reading material rather than cold feet, and is set on a wedding day that doesn’t exactly start on time. She’s reading a pamphlet that says she can’t leave her husband if he is ever found to be criminally insane. In the meantime, he learns that he might be held financially liable for any debts she might accrue. That idea, which is remarkably straightforward but incredibly disruptive, sets off a series of discussions that are less about love and more about legal procedures, emotional concessions, and moral failings.

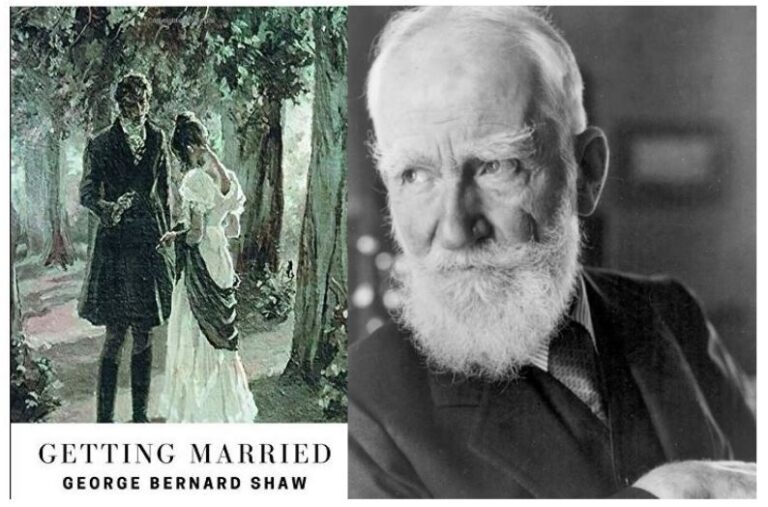

George Bernard Shaw’s “Getting Married”

| Title of Play | Getting Married |

|---|---|

| Author | George Bernard Shaw |

| Year Premiered | 1908 |

| Genre | Comedy of Manners |

| Central Theme | The legal, emotional, and societal conflicts surrounding marriage |

| Key Characters | Edith Bridgenorth, General Bridgenorth, Lesbia Grantham, Bishop of Chelsea |

| Major Motifs | Divorce law reform, personal freedom, gender roles, institutional satire |

| Setting | Bishop of Chelsea’s kitchen during a wedding gathering |

| Notable Insight | Challenges traditional marriage by offering legalistic and emotional critiques |

Shaw’s play does a remarkable job of exposing the more intricate workings of marriage by removing its ceremonial layers. Shaw applied logic like a crowbar to the topic, whereas the majority of playwrights of his time approached it with either gentle reverence or moral punishment. For example, the bishop proposes a return to marriages based on Roman contracts. Because of social expectations, some people, like the eloquently defiant Lesbia Grantham, completely reject marriage and the idea of becoming a household fixture.

Shaw was able to draw attention to the brittle and frequently incongruous expectations that are placed on couples by using satire. Getting Married argued that love shouldn’t be constrained by antiquated laws during a time when divorce was both socially taboo and legally complex. He revealed how many marriages were based on property law and public opinion rather than partnership through an uncompromising legal lens.

Shaw’s refusal to reduce marriage to failure or fairy tale is especially inventive. He views it as a dynamic institution that needs to change rather than be stuck in a rut. Therefore, this play is more of a calculated intervention than an indictment. He asked his audience to reconsider marriage’s foundation rather than reject it completely by promoting discussion among his characters.

Shaw’s arguments seem especially pertinent in the current era, given the trends toward cohabitation, prenuptial agreements, and marriage equality. His appeal for choice and clarity over mindless tradition speaks to today’s couples, who are more interested in customized contracts than pre-made ones. His questions about gender roles, such as why a woman should marry for security and why a man should take on financial dominance, are still relevant in discussions concerning labor division and economic equity in partnerships today.

The play uses witty dialogue and a setting that is remarkably cohesive to create tension through ideas rather than action. Even though the entire scene is set in a single room, the scope of the intellectual discussion feels remarkably broad. Shaw’s conviction that good ideas can be just as dramatic as sword fights or scandals is reflected in this tightly bound structure, which is reminiscent of the classical unities of Greek drama.

The way that young couples today deal with their own premarital doubts may be one of the most remarkably similar dynamics. Today’s partners browse prenuptial PDFs and counseling articles, just as Edith and Cecil took a moment to read their individual pamphlets. Nowadays, many people consider that intentional pause—which is frequently advised by financial advisors or therapists—to be a healthy step. Shaw foresaw it with remarkable accuracy, arguing that being aware of the dangers of marriage is a sign of maturity rather than a betrayal of love.

Marriage also experienced new forms of stress during the pandemic. Financial strain, communication breakdowns, and the unequal distribution of emotional labor between spouses were all made clear by confinement. Shaw had already warned about the dangers of being “shut up in one room” forever a century earlier. Shaw incorporates this idea through the contrasting paths and viewpoints of his characters, which is especially evident when you take into account how many contemporary therapists now stress distinct identities and routines as the cornerstones of a solid marriage.

Getting Married continues to be a curiously underutilized platform for social commentary among celebrities. Getting Married offers much more social provocation than Pygmalion, which dominates stage revivals along with its musical offspring, My Fair Lady. One wonders how celebrities who are vocal about gender, marriage, and personal preference, like Emma Thompson and Daniel Radcliffe, might respond to such a script in the modern era. Perhaps because it doesn’t cater to everyone, it hasn’t been included in big-budget movie adaptations. It analyzes the institution rather than praising it.

Shaw successfully foresaw the “conscious uncoupling” era by almost a century by highlighting how people commit to marriage too quickly while avoiding crucial discussions—legal, psychological, and social. His insistence that everything, including love, must be viewed through the prism of justice and liberty is very similar to the ideals guiding contemporary partnerships. He believed that marriage was neither intrinsically evil nor sacred. It needed to be revised, just like any other contract.

As cohabitation rates rise, divorce awareness increases, and a generation questions everything from state-sanctioned unions to monogamy, Getting Married becomes more than just a play—it becomes a tool. Instead of encouraging rote participation, it promotes critical analysis.

Shaw created something immensely adaptable by fusing legal theory with social criticism: a work that is equally enlightening, entertaining, and critical. By using this especially creative method, he provided theater with a unique fusion of reason and compassion, giving viewers a platform for introspection rather than fantasy.